Choosing Mathematical Symbols

A guide to choosing clear, memorable notation in mathematical writing.

When choosing symbols for mathematical objects (variables, sets, etc.), the best choices are

- descriptive

- consistent with conventions

- easily distinguished from other notation in use

Regarding the choice of symbols, Paul R. Halmos wrote [1]:

Good notation has a kind of alphabetical harmony and avoids dissonance. Example: either $a x+b y$ or $a_1 x_1+a_2 x_2$ is preferable to $a x_1+b x_1.$ Or: if you must use $\Sigma$ for an index set, make sure you don’t run into $\sum_{\sigma \in \Sigma} \sigma.$

This document contains guidelines for picking good symbols and examples to shorten the process.

Choosing a Symbol Based on the Starting Sound

When choosing a symbol, it is helpful to choose it such that there is a connection between the symbol and its meaning. The most basic approach is to use the Latin character that starts a word related to the symbol’s meaning, such as $g$ or $G$ for gravity. After exhausting the Latin alphabet, the Greek alphabet can be used. The name of each Greek letter generally starts with the sound it makes. For instance, gamma ($\gamma$ and $\Gamma$) makes a “g” sound, so it would be a reasonable choice for a gravity symbol if $g$ and $G$ are already used elsewhere. In the following table, the second column lists possible choices of symbols to represent a object that has a name or description that starts with the sound or letter given in the first column.

| First letter/sound | Symbols |

|---|---|

| ‘a’ as in “ape” or “apple” |

$a, A, \alpha$ (\alpha), $\aleph$ (\aleph)

|

| ‘b’ |

$b, B$, $\beta$ (\beta)

|

| ‘d’ (’distance’) |

$d, D$, $\delta$ (\delta), $\Delta$ (\Delta). Avoid $d$ for quantities that might appear in derivatives (for a quantity $d$, the notation "$dd/dt$ is confusing).

|

| ‘e’ as in “eat” or “egg” |

$e, E$, $\eta$ (\eta)

|

| ‘f’, 'ph’ as in “first” |

$\phi$ (\phi), $\varphi$ (\varphi), $\Phi$ (\Phi), $f$, $F$

|

| ‘g’ (‘good’) |

$g$, $G$, $\gamma$ (\gamma), $\Gamma$ (\Gamma)

|

| ‘j’ (’James’, ‘gee’) | $j, J$, $g$, $G$ |

| ‘k’ (’king’, ‘compact’) |

$k, K, c, C$, $\chi$ (\chi. Makes a hard "k" sound in Greek)

|

| ‘l’ (’lemma’, “Lie”) |

$l, L$, $\ell$ (\ell), $\lambda$ (\lambda), $\Lambda$ (\Lambda). The symbol $\ell$ (\ell) is generally preferable to $l$ (l), as it’s less likely to mistaken for a $1$ (1) and vice versa.

|

| ‘m’ |

$m$, $M$, $\mu$ (\mu)

|

| ‘n’ |

$n$, $N$, $\nu$ (\nu)

|

| ‘o’ |

$o$, $O$, $\omega$ (\omega), $\Omega$ (\Omega)

|

| ‘p’ |

$p, P$, $\pi$ (\pi), $\Pi$ (\Pi)

|

| ‘r’ (’radius’) |

$r, R$, $\rho$ (\rho), $\varrho$ (\varrho)

|

| ‘s’ (’see’, ‘psychic’, ‘cease’) |

$s, S$, $\psi$ (\psi), $\Psi$ (\Psi), $\sigma$ (\sigma), $\varsigma$ (\varsigma), $\Sigma$ (\Sigma), $c$, $C$, $\xi$ (\xi), $\Xi$ (\Xi)

|

| ‘t’ (’tensor’, ‘time’) |

$t, \tau$ (\tau), $T$

|

| ‘th’ |

$\theta$ (\theta), $\Theta$ (\Theta), $t, T$, $\mathrm{Th}, \mathrm{th}$, $\vartheta$ (\vartheta)

|

| ‘u’ (’you’, ‘young’) | $u, U$, $y$, $Y$. Lowercase upsilon "$\upsilon$" should be avoided due to the similarity to lowercase vee "$v$". |

| ‘v’ | $v, V$ |

| ‘w’ | $w, W$ |

| z | $z, Z, \zeta$ (\zeta)

|

Modifying a Symbol to Create a New, Related Symbol

Suppose we are using the symbol $x$ and want to introduce a second symbol that is strongly related to $x.$ The following modifications can be used to create a new symbol.

| Example | Description |

|---|---|

| $x^1, x^{(2)}, x^a, x^*, x^\circ$ | Superscript. Numbers should be avoided when they could be confused with exponents. |

| $x_1, x_a, ...$ | Subscripts. Having more than two layers of subscripts should be avoided to preserve readability. |

| $x', x'', x'''$ | Prime notation. Commonly used for derivatives, so avoid when there may be confusion. Use at most three tick marks. |

| $x_{I}, x_{II}, x_{III}, x_{IV}$ | Annotate with Roman Numerals. I’ve never seen this notation in a publication, but I use it within my scratch work to keep track of different iterations while I develop my work. If, say, I’m trying to find a set that satisfies some properties, I might notation them $A_I, A_{II}, ...$, until I find one that works. Then, I would simply call the final choice $A$. |

| $x \mapsto \hat{x}, \tilde{x}, \overline{x}, \underline{x}$ | Add annotations above or below. |

| $x \mapsto X$ $F \mapsto f$ |

Change capitalization |

| $x \mapsto \mathrm{x}, \mathbf{x}$ $X \mapsto \mathcal{X}, \mathbb{X}, \mathbf{X}, \mathscr{X} , \mathfrak{X}$ |

Change the font. This should be used with caution because the difference between certain fonts will not be obvious to all readers, especially in handwritten text. See note below. |

| $x_{\textrm{label}}$, $x^{\textrm{label}}$ | Include text labels. This is a heavy-handed approach that is tedious to write, but it does not require remembering another piece of notation so it might be desirable in presentations where the audience cannot go back to review the notation. Avoid for symbols that occur often. |

| $a \mapsto b, \text{or } x\mapsto y$ | Use letters that are adjacent in the alphabet. |

| $x \mapsto p_x, A_x$ | Juxtaposition with another symbol. Use $x$ as a label for another symbol |

| $V \mapsto \Lambda$ | Change the [orientation of the symbol](https://tex.stackexchange.com/questions/18157/rotating-a-letter). (This doesn’t work for symmetric symbols, such as $x$). |

| $x \mapsto \Delta x, dx, \delta x$ | Prefix with another symbol (typically, $\Delta x$ represents a change in $x$; $\delta x$ represents a small but finite change in $x$, and $dx$ is used to represent the change in $x $ in the limit as the change goes to zero.) |

| $x \mapsto [x]$, $\{x\}$, $\|x\|$ | Brackets. Use with caution as most brackets have existing meanings. |

| $x \mapsto f(x)$ | Function notation. |

| $1 + x^2$ | Sometimes, a new symbol is not actually necessary. For instance, if the new symbol depends on $x,$ you can simply write it as a function of $x$. |

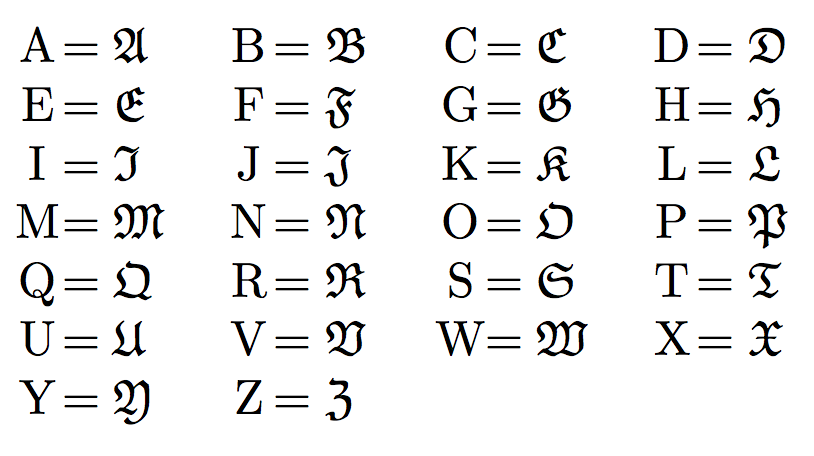

Using Different Fonts

In addition to the default capital Latin characters ($A$, $B$, $C$), etc., LaTeX provides script (\mathscr) characters $\mathscr{A}$, $\mathscr{B}$, $\mathscr{C}$; calligraphy (\mathcal) characters ($\mathcal{A}$, $\mathcal{B}$, $\mathcal{C}$); and Fraktur (\mathfrak) characters $\mathfrak{A}$, $\mathfrak{B}$, $\mathfrak{C}$. Many letters are different enough in each style that readers can be expected to recognize them as distinct symbols. For example, one can safely use $L, \mathcal{L}$, and $\mathfrak{L}$ in the same document without much risk of confusion (although, if you are writing these characters by hand, that is a different story!).

However, many of the Fraktur characters are easily confused with each other so care should be used to avoid mixing, say $\mathfrak{I}$ and $\mathfrak{J}$ in the same document.

Placing Modifiers Over $i$ and $j$

When placing modifiers over $i$ and $j$, such as $\hat{i}$ or $\bar{j}$, the dots in the letters creates a crowded appearance with the modifier.

To fix this, replace i and j with \imath and \jmath, which renders the respective letters without dots, e.g., $\imath$ and $\jmath$.

The resulting combination with hats and bars is more pleasing: $\hat{\imath}$ (\hat{\imath}) and $\bar{\jmath}$ (\bar{\jmath}).

In this context, I prefer \bar{\jmath}, which is rendered as $\bar{\jmath}$, instead of \overline{\jmath}, which is rendered as $\overline{\jmath}$, because the line is better aligned with the top of the character.

Choosing Symbols Based on Type of Mathematical Object

There are conventions for notating certain types of mathematical objects. The following rules are not universally accepted, but are merely taken from my personal observations.

| Type of Object | Common Notation Classes |

|---|---|

| Set |

Capital Latin or Greek ($A, B, C, \Lambda$); Calligraphy ($\mathcal{A, B, C}$); Blackboard bold ($\mathbb{R, N, Z}$)—typically reserved for well-known sets; Script ($\mathscr{A, B, C}$)—commonly used for sets of sets; Set-builder notation: $\{a, b, c\}$ |

| Function |

Lowercase Latin: $d, f, g, h, u, v, w, x, y, z$ Lowercase Greek: $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ Capital Latin: $F, G, H$ Capital Greek: $\Gamma, \Theta, \Phi, \Psi, \Omega, \Xi$ Often the choice of symbol for a function matches the convention used for objects in the function’s codomain (range). |

| Vector | $x$ (x), $\boldsymbol{x}$ (\boldsymbol{x}), $\mathbf{x}$ (\mathbf{x}), $\vec{x}$ (\vec{x}), $\underline{x}$ (\underline{x}). In texts where students are newly acquainted to vectors, $\mathbf{x}$ or $\vec x$ is commonly used. The notation $\vec x$ has the advantage that it can easily be written by hand, but it makes equations more cluttered, especially when other annotations are added, such as $\dot{\vec{\widetilde{x}}}$. In advanced texts, $x$ is almost always used.

|

| Scalar | $a, b, c, x, y, z, \alpha, \beta, \gamma$. See notes on real numbers and integers, below. |

| Unitary Operation |

Prefix: $x\mapsto -x$, $f \mapsto \partial f$ Annotations: $f\mapsto \hat f, f\mapsto \tilde f, x\mapsto x^*$ Function notation: $x\mapsto f(x), f\mapsto \mathcal{L}\{f\}, x\mapsto \sin x$ Capitalization: $f \mapsto F$ Sub/superscripts: $x \mapsto x_{\text{new}}$ |

| Binary Operation | infix: $a+b$, $A\cup B$, $p \wedge q;$ function: $f(x, y);$ juxtaposition: $xy, \overset{x}{y}, \underset{x}{y}, x^y;$ brackets: $(x, y), \langle x, y\rangle.$ |

| n-ary Operation |

Prefix: $\Pi_{i=1}^n x_i$ (Abbreviated) infix: $x_1 + x_2 + \cdots + x_n$ Function: $f(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)$ Einstein Summation Convention: $v^i\frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}$ |

| Matrix |

Capital Latin or Greek: $A, B, C, \Gamma;$ Upright Capital Latin: $\mathrm{A, B, C, M}$; Bold Capital Latin: $\mathbf{A, B, C, M};$ Element-wise notation: $[a_{ij}]$, $[\sin(i\pi)\cos(j\pi)].$ |

| Sequence |

Abbreviated: $1, 1/2, 1/3, \dots;$ Sequence notation: $\{s_j\}_{j=1}^\infty;$ Juxtaposition (as a squence of heads/tails is represented in probability): $\text{HHTHT};$ Recursive: $x_{k+1} = r(1-x_k),$ Function: $i \mapsto 1/i.$ |

Real Numbers

Typically, lowercase Latin or Greek letters are used to represent real numbers. Less commonly, uppercase letters are used as well.

Several symbols, namely $\pi$ and $e$, have well-established meanings, so they should be avoided when there is any risk of ambiguity. The letters $\varepsilon$ and $\delta$ are frequently used to represent small positive numbers and capital letters such as $M$ or $R$ are sometimes used for large values.

For Latin letters, note that $e$ has a well-established usage as Euler’s constant. Be judicious in the use of $f, g, h$, which are commonly used for functions.

Avoid $i, j, k, m, n$ because they are commonly used for integers and avoid $l, o$ due to potential confusion with $1$ and $0$—the symbol $\ell$ can be used instead of $l$.

Integers (and Natural Numbers)

Typically, lowercase and (less frequently) uppercase Latin letters are used to represent integers. The letters $i, j, k, m, n$ are common choices, especially for indices. Choosing one of them offers a hint to the reader that the variable is an integer when they encounter it after its introduction. In some contexts, $i$ or $j$ is reserved for the imaginary unit $\sqrt{-1}$. The letters $a, b, c, d, p, q$ are also commonly used for integers but are also used as real numbers. Avoid $l, o$ (due to potential confusion with $1$ and $0$—$\ell$ can be used instead of $l$). A capital letter is useful to convey that an integer will be “large”, e.g., defining a sequence $x_i$ in $\mathbb{R}$ to be unbounded if “for every $M > 0$, there exists $i \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $x_i > M$.”

Variables vs. Constants

When it comes to variables and constants, I prefer to use the beginning of the alphabet for constants and the end for variables. In particular, I tend to use $a,$ $b,$ $c,$ $d,$ $p,$ $q,$ $r$ for constants and $t,$ $u,$ $v,$ $w,$ $x,$ $y,$ $z$ are for variables.

Example: Picking Notation for Upper and Lower Bounds

In this section we present a case study of picking symbols for the upper and lower bounds on a real number $x$. At first, we can simply take the first two letter of the alphabet.

\[a \leq x \leq b\]Using $a$ and $b$ is fine, but the connection of $a$ and $b$ with $x$ is not implied symbolically. We also have to pick two new symbols if we need to set bounds on another value, say $y$. To show the connection between $x$ and the bounds, we might instead pick

\[x_{lb} \leq x \leq x_{ub}.\]The use of italicized text for $lb$ and $ub$ is bad form, however. A better choice is

\[x_{\mathrm{lb}} \leq x \leq x_{\mathrm{ub}}.\]This choice is pretty good, but writing letter subscripts can get tedious and makes equations somewhat messy. y For this reason, I prefer to simply underline $x$ for the lower bound and overline $x$ for the upper bound.

\[\underline{x} \leq x \leq \overline{x}.\]This notation is (1) simple, (2) visually descriptive, and (3) does not require choosing new symbols for every upper and lower bound that is introduced. There are cases where $\overline{x}$ can cause confusing, however. Namely, if $x$ is a complex number, then $\overline{x}$ could be read as the complex conjugate.

Finding Symbols Based on Appearance

There are far too many symbols to possibly know all of them. In cases when you know how symbol looks and wish to recover the LaTeX code, you can use Detexify and the Mathpix Snipping Tool. To browse through available symbols, the Comprehensive Latex Symbol List provides a massive list of symbols.

References

[1] Norman E. Steenrod, Paul R. Halmos, Menahem M. Schiffer, and Jean A. Dieudonné, How to Write Mathematics. 1973. [2] N. J. Higham, Handbook of writing for the mathematical sciences, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1998.

COMMENTS

You can use your Mastodon account to comment on this article by replying to the associated post.